Stealing Time for My Own Mind

Dhamma Setu, Chennai — India

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in room alone,”

— Blaise Pascal.

My step mum thought I was going to rehabilitation, my friends thought I was on a fast-track to becoming a monk, and I was only half sure what to expect when I enrolled for a 10 day Vipassana meditation course in Chennai, India.

On and off and with mixed success I’ve been meditating for the last 3 years.

I was in the middle of a long-term travel across Asia and for a list of reasons as long as your arm, I felt it was a good time to do this.

Lacking Expectations

Before starting the Vipassana meditation course I did my best to resist reading up about it — I wanted to go in with as little expectations as possible.

There were two exceptions:

- Francis Irving ’s thoughtful piece ( link ).

- Sitting positions for mediation ( link ).

1] A Way Out of Suffering

Vipassana is considered to be the most accurately preserved technique for what Buddha taught us — to purify your mind, to eliminate tensions — namely cravings and aversions — and negativities that make us miserable.

This journey takes you over a Noble Eightfold Path that divides into 3 trainings:

- Sīla: The training of Moral Conduct

- Samādhi: The training of Concentration, Control of Your Mind

- Paññā: Wisdom, Insight, Total Purification of Your Mind

2] The Practice

/Aside:/ /The course leaders asked that we don’t share the Vipassana technique itself since there are a bunch of important stepping stones you need to take before the meditation can be practiced. What I’ve done here is pull out a few anecdotes from the 10 days that’ll give you a small window into some of the surprises, agony and insights I experienced./

If you’d rather, you can skip ahead to Section ❲3❳ “Vipassana & Beyond” for the reflective.

(Day: 1) Arrival

I met a guy from Canada called Mazen in Chennai — he was taking Vipassana too. We shared a cab to Dhamma Setu, just 20 minutes outside of Chennai.

When we arrived we were told to make our way to the dining hall. It reminded me of the dinner hall from my primary school. Beige walls, dated windows, simple furniture, a lingering smell of cleaning detergents.

I remember thinking the fridge looked like the one that rattles around in Requiem for a Dream.

After registration it was the introductory speech. First English, then Tamil. The girls sat the opposite side to the guys. The speakers were quite bad quality and the sound echoed around the room. You had to really sit forward to hear the words.

As of this point, the Noble Silence had started. No talking for the next 10 days. For the most part I was calm, but Wow, the task ahead:

- 12 hours of meditation each day

- Up at 4am

- Finish at 9:30pm

- No talking

- No mobile phones

- No internet

- No reading, no intellectual stimulation

- No exercise

- No eye contact — 100% solitude

- Separation from the opposite sex

- 2 simple meals per day (breakfast and lunch)

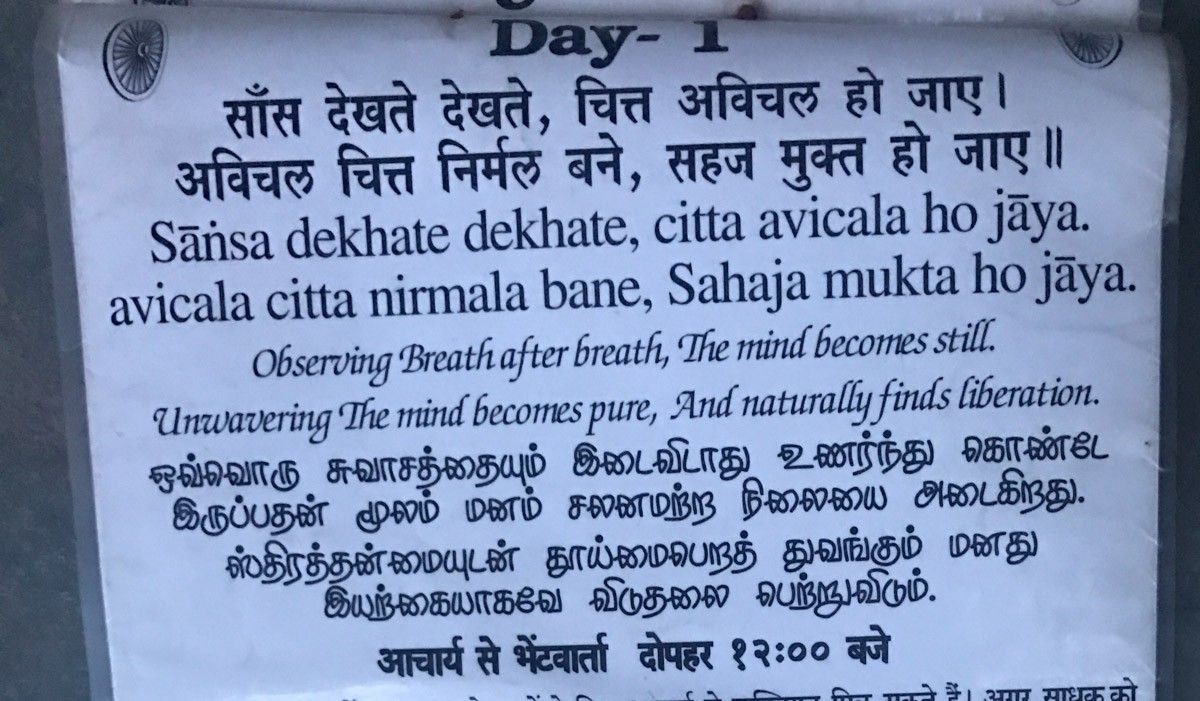

(Days: 1–3) The Training of Concentration

To develop our mental concentration, the first 3 days we exercised ānāpānā-sati — awareness of respiration.

To do this we had to identify and keep our minds focused on the sensations of breathing in and out from the area starting at the top of the nose, down each side of our upper lips — forming a triangle area.

We had to answer questions such as “was the breath:”

- long or short?

- heavy or light?

- rough or subtle?

On day 3, we were expected to bring our attention down to an even smaller area, the philtrum — the small area underneath your nose and above your top lip.

This is to sharpen the mind so it can observe the subtlest sensations within the body.

Simple Does Not Equal Easy

All we were expected to do was keep our attention on these areas while observing the breath. Sensations that arose and passed away. Sounds simple, is simple, but this was was one of the hardest 3 days of my life.

One of the biggest surprises was just how much work was needed to direct my attention and keep it fixed on the breath.

The popular idea that meditation is time for inactivity and relaxation never felt so far away.

A Circus of Distraction

The first thing that the strikes you is just how distracted you are. I could go for 20–30 minutes being completely derailed by a thought — a plan for the future, a memory from the past. I only had to do one thing — observe sensations — but it was more than difficult to stay focused.

Distractions dragged me right through the emotional rainbow. Just like life itself, some good, some bad, some happy, some sad thoughts frothed-up to the surface.

According to the Vipassana Meditation book I picked-up, this is an expected part of the journey:

Another surprise is that, to begin with, the insights gained by self-observation are not likely to be all be pleasant and blissful. Normally we are selective in the view of ourself. When we look into the mirror we carefully strike the most flattering pose… In the same we have a mental image of ourselves which emphasises the admirable qualities, minimises defects, and omits some sides of our character all together. We see the image we wish to see, but not the reality…

But right at the heart of Vipassana is observing reality — seeing things for the way they are. Instead of a carefully edited self-image, you’re confronted with the whole uncensored truth.

After working through the distractions — persistently bringing my attention back to my breath — occasionally I could go for 10, 20 minutes with my attention resting on my breath. The hour meditation sessions began to pass by much faster.

Sometimes I’d experience hallucinations. A mixture of peoples’ faces and places from my childhood.

The better I got at resting my attention in one place the more I began to feel an inner calm — as if a huge weight had lifted from my shoulders.

By day 4, I felt a much stronger presence of mind.

At the end of the morning meditation I would walk outside and hear the sounds of nature so clearly, without distraction, without chasing thoughts, without an inner monologue.

My mind had been brought into the present.

The Physical Agony

Another surprise is the agony you go through sitting in one place for so long. I had a small meditation mat.

I sat crossed-legged or half lotus while meditating.

At 4:30am, the first 20 minutes is relatively comfortable. As you hit the 30 minute mark, aches and pains begin to show their faces. By 40 minutes the pains turn into agony.

Unlike running across a rugby field with your adrenaline running high, you’re sedentary — sitting still — and you have nowhere to escape the pain.

If there’s one thing that got me through this, it would be the older mediators. At a guess, there were a few old boys taking the course that were at least 70. If they could work through this, then what the fuck excuse did I have?

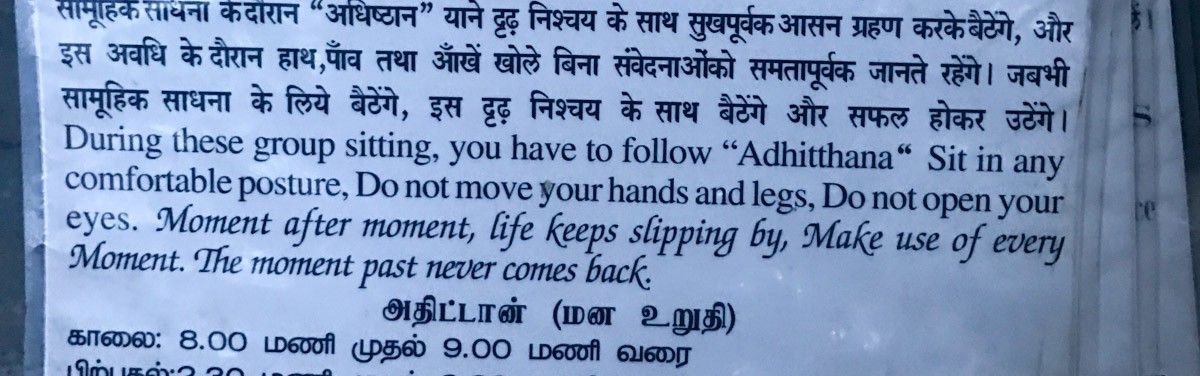

(Day: 5) Adhiṭṭhāna

Adhiṭṭhāna has been translated as “decision,” “resolution,” “self-determination,” “will”[1] and “resolute determination.”

By day 4 we entered the Adhiṭṭhāna sessions where you’re expected to meditate for an entire hour without moving. No gentle reshuffling to a different position to take the inescapable aching pain out of your knee / leg / back. No opening your eyes. Nothing. Just still.

What surprised me about these sessions was how it forced you to bring your mind to a state of balance.

The word used to describe the state of mind is Equanimity:

“is a state of psychological stability and composure which is undisturbed by experience of or exposure to emotions, pain, or other phenomena that may cause others to lose the balance of their mind”

If you lost the balance, the physical pain would become too intense, you’d panic, you’d become overwhelmed and you’d have to move.

A Quiet & Balanced Mind Can Hear Its Body

One of the things I noticed during the 10 days was how your feelings and emotions are reflected as sensations in your body.

When I experienced a thought that made me feel sad, I felt it right in the middle of my solar plexus. When I feel stressed, I felt tension right around the back of my head. When I feel anxious, I felt it in my stomach and facial area. The list goes on.

Meditation brought my mind to a place where I could identify those subtle sensations.

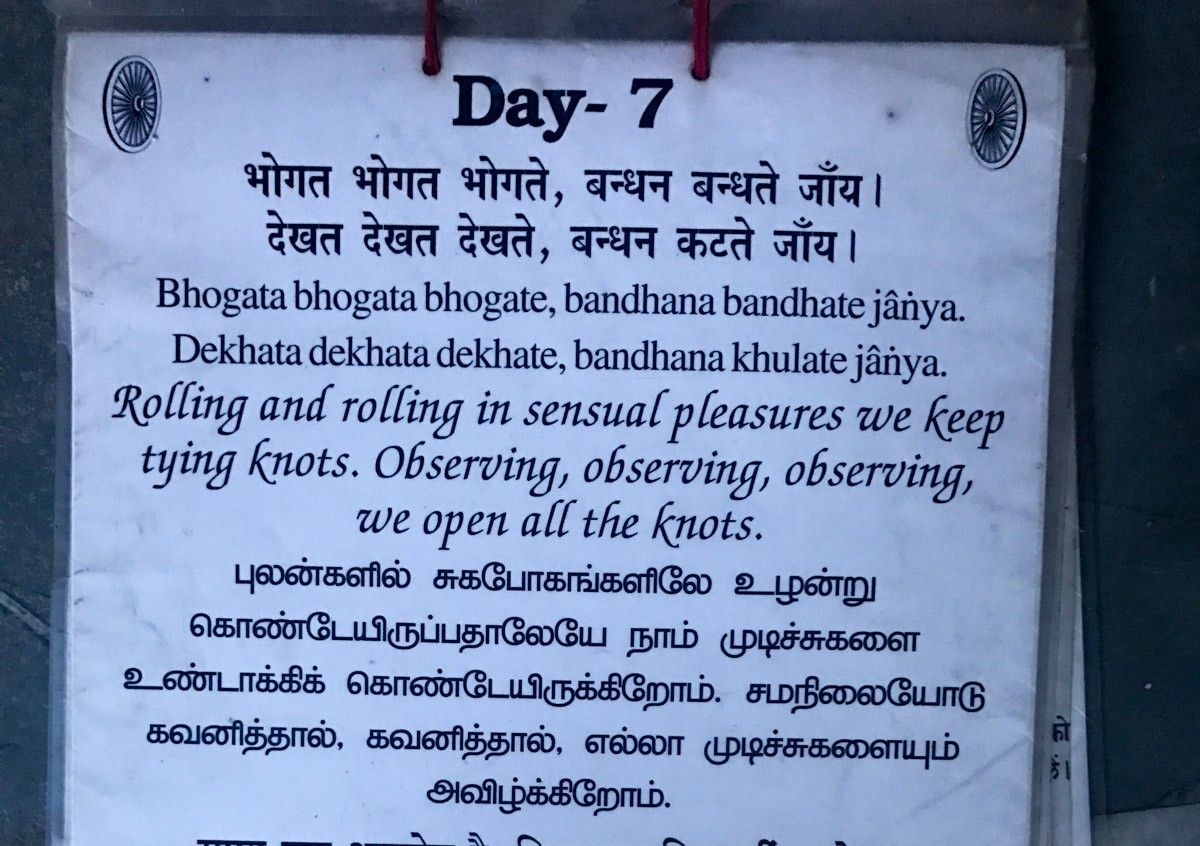

(Day: 7) The Power of Observation

Possibly the most powerful experience of the whole 10 days happened on day 7. I’d managed to follow through on all Adhiṭṭhāna sessions (no moving, no eye opening for the hour) up until this point, but during the mid morning session of day 7, about 10 minutes in, I began feeling a sharp pain in my left knee.

I’d sat in a bad position that was putting a lot of stress on my knee.

Rightly or wrongly, I was determined to not let the pain get the better of me — I wanted to make the whole session without moving.

As I hit the 20 minute mark, the pain in my knee was sharp and throbbing. For a few moments I tried to think about something else to avert the pain; this goes completely against the principles of Vipassana.

This was bad. I remember being close to tears — in pain, in frustration.

Remembering the fundamental principles of Vipassana (observation and a balanced mind), I started observing the pain. Trying my best to keep my mind calm and balanced, I began answering questions like:

- Is it a pulsing pain, or is it a constant pain?

- Is it a sharp pain, or is it an ache?

- Exactly whereabouts on the knee is the pain coming from? Is it the same pain on the top as it is on the bottom?

- Are there any other sensations that are arising over the knee?

I kept cycling over those questions again and again.

As I was working through answering the questions as objectively as possible — without reacting to the pain — I couldn’t believe what happened before me.

The pain faded away.

I’d gone from complete agony, to feeling comfortable and calm. I remember my knee feeling warm and a subtle tingling sensation spreading over my legs but that was it. The agony had passed away.

This was the power of observation.

For me, this was the biggest takeaway from Vipassana. Instead of blindly reacting to sensations in the body — which makes us agitated and miserable — we can observe them with a balanced mind. As we continue to observe them objectively — without reaction — the sensations begin to unravel.

They become less intense, they affect us less.

And since the body’s sensations are the direct bridge to the mind’s emotions, observing them unravels their intensity too — until our minds are balanced and calm.

We can unravel the /craving/ sensations for sugar, for alcohol, for cigarettes, for attention and all the other primate bullshit.

We can unravel the /aversion/ to public speaking, to running that extra mile, to having that difficult conversion, to taking action.

I used to look up at this triangle formation the palm trees made. Is there a hidden message there? :)

(Day: 10) Course Completion

As the noble silence lifted and the course came to a close, I bullet-pointed how I felt:

- A strong sense of calm

- More awake and alert

- I needed to sleep less

3] Vipassana & Beyond

My big takeaways and some loose ends I’m trying to get my head around:

Deleting your passion

Ultimately, I see Vipassana is a teaching of dispassion. Passion is the enemy of a balanced mind. If I follow Vipassana properly, I shouldn’t fall in love with a piece of music. Doing so leads to cravings, which creates attachment and attachment leads to misery.

So just as Vipassana expects us to not react to negative emotions, we’re expected to not react to positive emotions too.

I work in startup companies where the life of the company is almost completely dependent on the relentless hard work, determination and /passion/ of the founders. To my mind, the latter is the most essential ingredient.

What happens when passion is taken out of the equation? Does the same amount of hard work go in?

If founders thought about things clearly wouldn’t they see that the deck is stacked against them and that they’d be better off taking a job in the city?

A good friend Francis Irving raises a similar point about Vipassana meditation:

“My big problem with it culturally is the way it devalues the senses and the wonder of the physical world. Isn’t our will to power also glorious? Where is the joy in dancing, in loving, in craving, in living? Can’t a meditation embrace this, not cut it out?”

Being Present

I found ānāpānā-sita — the training of concentration to be fruitful. I’ve often wondered what the zen-types meant when they point out that being present or presence of mind is bliss.

Once you develop the awareness it’s fascinating to realise how distracted in thought you actually are throughout the day — experiencing an orgasm is probably one of the few exceptions.

Meditating to bring the mind into the present was positive for me.

It’s calming, it helps you think clearly and it connects you to your surroundings. You can remember peoples’ names, you can see things clearly.

Use the past to inform your present, but don’t live in the past — and all that jazz.

I think I had a brief taste of this during the course, and it’s something I’ll continue to work on.

Gross Sensations Saṅkhāra?

I value how Vipassana concentrates on the practical, the experiential, the see for yourself teachings of Buddha.

There are however a few exceptions, even if we set aside the widely debated assumption of rebirth, a supernatural phenomenon.

Goenka — the course teacher — explains that the gross sensations (aches, pains) you experience when meditating are your saṅkhāras — mental conditionings from either this life or former lives.

According to the teachings, saṅkhāras — mental conditionings — are impurities of the mind that distort our view of reality, making us agitated and unhappy.

The goal is to use Vipassana meditation to remove our stock of current and past saṅkhāras — this brings us to liberation, a pure and balanced mind.

In a QA Goenka answers:

Do sankharas mainly come out as pain?

“Not necessarily pain, they can manifest in different ways. They can come out as heat, they can come out as pressure, throbbing, as subtle vibrations. According to the type of sankhara, that type of sensation there will be.”

For me, this is a bit of a water jump.

Unlike the emotion to sensation connection you can experience for yourself — there’s no experience or rationale explanation that connects the saṅkhāras to physical pain.

Particularly when coupled to notions of previous lives, the idea that saṅkhāras are reflected as physical pain during Vipassana mediation seem a bit abstract to me.

Pinpointing the Cause of Calm

For all of the positive outcomes that I felt after taking the Vipassana course, initially I found it difficult to pinpoint what the cause was. Thinking about it, it could have been:

- The solitude — no social pressure, no burning energy communicating with others

- Unplugging from the internet

- Avoiding almost all forms of intellectual stimulation (reading, writing, sketching, planning)

- The environment

- The Vipassana meditation itself

It’s now been over 4 months since I took the course. Now I’m confident that my sense of calm, positivity and mental alertness after the Vipassana 10 day course was in-fact a direct result of the meditation.

I say this because during 6 months of travel in India I’ve been fortunate to experience days — even weeks — where I’ve been unplugged from the internet as well as a few days trekking in solitude, but I don’t report the same experiences as the days where I’ve meditated.

Return on Investment

“My favourite things in life don’t cost any money. It’s really clear that the most precious resource we all have is time.”

— Steve Jobs

Time indeed is our scarcest resource. Even with this in mind, I’m happy I invested time working on Vipassana.

For me, the 10 day course was an outline of the work you have to do going forward, not job done. Vipassana is a lot of work, and I’m not 100% sure I will — or even want to — complete the path to full liberation.

That said, I do see that certain steps along the path will be good for me to follow — particularly the training of concentration. Today we are distracted people and I worry that in a world where Silicon Valley is in a race to the bottom of your brain stem, things could get a tad worse.

The presence of mind and calmness I’ve experienced with mediation is a slam dunk for me — completely worthy of the time invested.

Waking Up

The more life experience I get, the more I believe anything that improves your awareness is good. Ignorance for the most part is a problem.

Awareness of your actions, your feelings, your intentions, your cravings, your aversions puts you in the driving seat.

It’s waking up.

Awareness gives you a clear path to make the changes you need to improve yourself. Or — for those lucky ones — the clarity you need to know that you’re already a brilliant person.

Vipassana helped to develop my awareness, it woke me up.

And for that I’m grateful.

Are You Fine?

I’d recommend taking a Vipassana Meditation Course if you are someone who is:

- Interested in learning meditation — a Vipassana 10 day course will serve as a brilliant crash course.

- Constantly feeling agitated, unsettled, discontent with yourself, others, your possessions — the time to reflect and find your inner calm will be good for you.

- Distracted or stressed — the ānāpānā — training for concentration will help to bring your mind into the here-and-now, to the present, which is calming and awakening.